2.5: The Certiorari Process

- Page ID

- 24096

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)- Understand the Supreme Court’s jurisdiction, including what kinds of cases are selected for review.

- Explore what happens when lower courts of appeal disagree with each other.

- Learn about the Supreme Court’s process in hearing and deciding a case.

Video Clip: The U.S. Supreme Court

(click to see video)

The Supreme Court’s jurisdiction is discretionary, not mandatory. This means the justices themselves decide which cases they want to hear. For the justices to hear a case, the losing party from the appeal below must file a petition for a writ of certiorari. During the 2008 term (a term begins in October and ends the following June), the Supreme Court received approximately 7,700 petitions. Of these, about 6,100 were in forma pauperis, leaving only approximately 1,600 paid petitions. In forma pauperis petitions are filed by indigent litigants who cannot afford to hire a lawyer to write and file a petition for them. Supreme Court rules permit these petitions to be filed, sometimes handwritten, without any filing fees. These petitions are typically filed by prisoners protesting a condition of their detention or a defect in their conviction and are quickly dismissed by the Supreme Court. Not all in forma pauperis petitions are meritless, however. In the case of Gideon v. Wainwright, Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963). a poor defendant convicted of burglary without being represented by a lawyer filed a handwritten in forma pauperis writ of certiorari with the Supreme Court. The Court granted the writ, heard the case, and ruled that Gideon was entitled to have a lawyer represent him and that if he could not afford one, then the government had to pay for one. Gideon was retried with a lawyer’s assistance, and he was acquitted and released.

Of the 7,700 petitions filed in the 2008 term, 87 cases were eventually argued. With such a large number of petitions filed, and a less than 1 percent acceptance rate, what kind of cases do the justices typically grant? Remember, the Supreme Court is a court of discretionary jurisdiction. It does not exist as a court to right every legal wrong, or to correct every social injustice. Typically, the cases fall into one of three categories. The first category is a case of tremendous national importance, such as the Bush v. GoreBush v. Gore, 531 U.S. 98 (2000). case to decide the outcome of the 2000 presidential election. These cases are rare, but they dominate headlines on the Supreme Court. Second, the justices typically take on a case when they believe that a lower court has misapplied or misinterpreted a prior Supreme Court precedent. This category is also fairly infrequent. By far, the majority of cases granted by the Supreme Court fall into the third category, the circuit split.

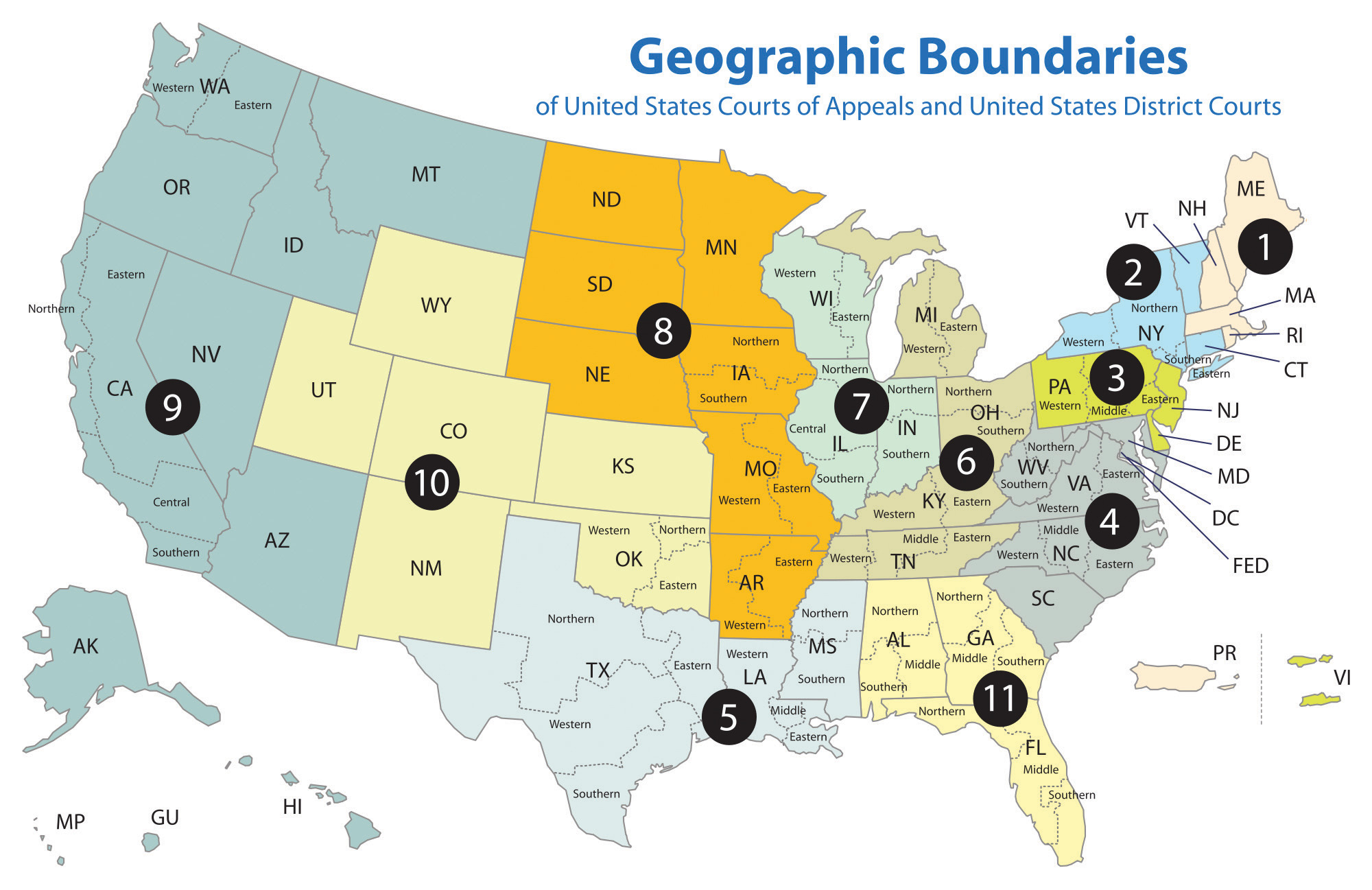

Recall that there are thirteen circuit courts of appeals in the United States (see Figure 2.5.1 "Geography of U.S. Federal Courts"). Eleven are divided geographically among the several states and hear cases coming from district courts within their jurisdiction. Thus, for example, someone who loses a case in federal district court in Pennsylvania will appeal his or her case to the Third Circuit Court of Appeals, while a litigant who loses in Florida will appeal his or her case to the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals. In addition to the eleven numbered circuit courts, there are two additional specialized courts of appeals. They are both seated in the District of Columbia. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit is a specialized court that mainly hears appeals involving intellectual property cases, such as those involving patent law. Decisions by this court on patent law are binding on all district courts throughout the country, unless overruled by the Supreme Court. The second specialized court is the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. Although this appellate court has the smallest geographical area of any court of appeal, it is a very important court as it hears cases against the federal government and the myriad federal agencies in Washington, DC. Chief Justice Roberts, as well as Justices Scalia, Ginsburg, and Thomas, served on this important court before being appointed to the Supreme Court.

A circuit split arises when the circuit courts of appeals disagree with each other on the meaning of federal law. Let’s assume that two similar cases are being decided in federal district court at the same time, one in California and the other in South Carolina. The cases present similar facts and involve the same federal law passed by Congress. Both cases are appealed—the California case to the Ninth Circuit and the South Carolina case to the Fourth Circuit. On appeal, it’s possible that the two appellate courts may come to opposite conclusions on what the law means, especially if Congress has recently passed the law. Since the circuit court of appeal decision is binding for that circuit, the state and meaning of federal law is different based on where a citizen lives. The Supreme Court is therefore very likely to grant certiorari in this case to resolve the split and decide the meaning of the law for the entire country.

When a petition for writ of certiorari is filed with the Supreme Court, the party that won the case in the appeal below (called the respondent) files an opposition. Together, these two documents are considered by the justices during one of their weekly conferences to decide whether or not the case should be granted. As previously discussed, cases that fall into one of three categories are generally granted, while others are dismissed. The conference works on the rule of four—only four justices (a minority) need to agree to hear a case for the petition to be granted. The vast majority of cases are dismissed, which means the decision of the lower court stands.

Each Supreme Court justice is permitted to hire up to four law clerks every term to assist with his or her work. These law clerks are typically new attorneys from the nation’s best law schools. Being selected as a clerk is obviously very prestigious, and the job is reserved for the brightest young legal minds. Many justices rely on their clerks to read the thousands of filed petitions and to make recommendations on whether or not to grant the case. This arrangement, called a cert pool (the clerk assigned to the case writes a memo that is circulated to all the justices), has been criticized as giving too much power to inexperienced lawyers. Participation in the cert pool is voluntary and not all the justices participate. Justice Alito, for example, does not participate, and his clerks read all the incoming petitions independently. Until his retirement, Justice Stevens also did not participate in the cert pool process.

If a petition is granted, the parties are then instructed to file written briefs with the Court, laying out arguments of why their side should win. At this point, the Court also allows nonparties to file briefs to inform and persuade the justices. This type of brief, known as an amicus brief, is an important tool for the justices. Many cases before the Supreme Court are of tremendous importance to a broad array of citizens and organizations beyond the petitioner and respondent, and the amicus brief procedure allows all who are interested to have their voice heard. For example, in the 2003 affirmative action cases from the University of Michigan, more than sixty-five amicus briefs were filed in support of the university’s policies, from diverse parties such as MTV, General Motors, and retired military leaders.

www.vpcomm.umich.edu/admissions/legal/gru_amicus-ussc/um.html

The University of Michigan affirmative action cases drew national attention to the practice of colleges and universities using race as a factor in deciding whether or not to admit a college applicant. The Supreme Court ultimately held that race may be used as a factor but not as a strict numerical quota. The Court was aided in its decision by numerous amicus briefs urging it to find in favor of the university, including briefs filed by many corporations. Click the link to read some of these briefs and to understand why these companies are strong supporters of affirmative action.

After the justices have read the briefs in the case, they hear oral arguments from both sides. Oral arguments are scheduled for one hour, in the main courtroom of the Supreme Court building. They are open to the public but not televised. Members of the press are given special access on one side of the courtroom, where they are permitted to take handwritten notes; no other electronic aids are permitted. During the oral arguments, the justices are interested not in the attorneys repeating the facts in the briefs but rather in probing the weaknesses of their arguments and the implications should their side win. The justices typically hear two or three cases a day while the Court is in session. Before each day’s session, the marshall of the court begins with the invocation in "Hyperlink: Oyez.org".

After the oral arguments, the justices once again meet in conference to decide the outcome of the case. Unlike the other branches of government, the justices work alone. No aides or clerks are permitted into their conferences. Once they decide which side should win, they begin the task of drafting their legal opinions. The opinions are the only way that justices communicate with the public and the legal community, so a great deal of thought and care is given to opinion drafting. If the chief justice is with the winning side, he or she decides which justice writes the majority opinion, which becomes the opinion of the Court. The chief justice can use this assignment power wisely by assigning the opinion to a swing or wavering member of the Court to ensure that justice’s vote doesn’t change. If the chief justice is in the minority, then the most senior of the justices in the majority decides who writes the majority opinion. Dissenting justices are entitled to write their own dissenting opinions, which they do in hopes that one day their view will become the law. Occasionally, a justice may agree with the outcome of the case but disagree with the majority’s reasoning, in which case he or she may write a concurring opinion. After all the opinions are drafted, the Court hands down the decision to the public. Except in very rare instances, all cases heard in a term are decided in the same term, as the Court maintains no backlog.

Key Takeaways

The Supreme Court has discretionary jurisdiction to hear any case it wishes to hear. Every year, the chance of having the Supreme Court hear a particular case is less than 1 percent. The Supreme Court is more likely to hear a case if it involves an issue of national importance, if the Court believes a lower court has misinterpreted precedent, or if the case involves a split in the appellate circuits. A circuit split occurs when two or more federal circuit courts of appeals disagree on the meaning of a federal law, resulting in the law being different depending on where citizens live. Although it takes a majority of justices to vote together to win a case, only a minority decides the Court’s docket under the rule of four. The Supreme Court decides cases every term by reading briefs and amicus briefs and by hearing oral arguments. In any case, the Court may issue a majority opinion, dissenting opinions, and concurring opinions.

- Do you believe that Supreme Court oral arguments should be televised, as government proceedings are on C-Span? Why or why not?

- Do you think the Supreme Court should act more as a court of last resort, especially in serious cases such as capital crimes, or should the Supreme Court continue to accept only a very small number of cases?