2.1: Accounts

- Page ID

- 97788

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\(\newcommand{\avec}{\mathbf a}\) \(\newcommand{\bvec}{\mathbf b}\) \(\newcommand{\cvec}{\mathbf c}\) \(\newcommand{\dvec}{\mathbf d}\) \(\newcommand{\dtil}{\widetilde{\mathbf d}}\) \(\newcommand{\evec}{\mathbf e}\) \(\newcommand{\fvec}{\mathbf f}\) \(\newcommand{\nvec}{\mathbf n}\) \(\newcommand{\pvec}{\mathbf p}\) \(\newcommand{\qvec}{\mathbf q}\) \(\newcommand{\svec}{\mathbf s}\) \(\newcommand{\tvec}{\mathbf t}\) \(\newcommand{\uvec}{\mathbf u}\) \(\newcommand{\vvec}{\mathbf v}\) \(\newcommand{\wvec}{\mathbf w}\) \(\newcommand{\xvec}{\mathbf x}\) \(\newcommand{\yvec}{\mathbf y}\) \(\newcommand{\zvec}{\mathbf z}\) \(\newcommand{\rvec}{\mathbf r}\) \(\newcommand{\mvec}{\mathbf m}\) \(\newcommand{\zerovec}{\mathbf 0}\) \(\newcommand{\onevec}{\mathbf 1}\) \(\newcommand{\real}{\mathbb R}\) \(\newcommand{\twovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\ctwovec}[2]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\threevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cthreevec}[3]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfourvec}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\fivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{r}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\cfivevec}[5]{\left[\begin{array}{c}#1 \\ #2 \\ #3 \\ #4 \\ #5 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\mattwo}[4]{\left[\begin{array}{rr}#1 \amp #2 \\ #3 \amp #4 \\ \end{array}\right]}\) \(\newcommand{\laspan}[1]{\text{Span}\{#1\}}\) \(\newcommand{\bcal}{\cal B}\) \(\newcommand{\ccal}{\cal C}\) \(\newcommand{\scal}{\cal S}\) \(\newcommand{\wcal}{\cal W}\) \(\newcommand{\ecal}{\cal E}\) \(\newcommand{\coords}[2]{\left\{#1\right\}_{#2}}\) \(\newcommand{\gray}[1]{\color{gray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\lgray}[1]{\color{lightgray}{#1}}\) \(\newcommand{\rank}{\operatorname{rank}}\) \(\newcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\col}{\text{Col}}\) \(\renewcommand{\row}{\text{Row}}\) \(\newcommand{\nul}{\text{Nul}}\) \(\newcommand{\var}{\text{Var}}\) \(\newcommand{\corr}{\text{corr}}\) \(\newcommand{\len}[1]{\left|#1\right|}\) \(\newcommand{\bbar}{\overline{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bhat}{\widehat{\bvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\bperp}{\bvec^\perp}\) \(\newcommand{\xhat}{\widehat{\xvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\vhat}{\widehat{\vvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\uhat}{\widehat{\uvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\what}{\widehat{\wvec}}\) \(\newcommand{\Sighat}{\widehat{\Sigma}}\) \(\newcommand{\lt}{<}\) \(\newcommand{\gt}{>}\) \(\newcommand{\amp}{&}\) \(\definecolor{fillinmathshade}{gray}{0.9}\)Use the following as a self-check while working through Chapter 2.

- What is an asset?

- What is a liability?

- What are the different types of equity accounts?

- What is retained earnings?

- How are retained earnings and revenues related?

- Why are T-accounts used in accounting?

- How do debits and credits impact the T-account?

- What is a chart of accounts?

- Are increases in equity recorded as a debit or credit?

- Are decreases in equity recorded as a debit or credit?

- Does issuing shares and revenues cause equity to increase or decrease?

- Are increases in the share capital account recorded as a debit or credit?

- Are increases in revenue accounts recorded as debits or credits?

- Do dividends and expenses cause equity to increase or decrease?

- Are increases in the dividend account recorded as a debit or credit?

- Are increases in expense accounts recorded as debits or credits?

- How is a trial balance useful?

- What is the difference between a general journal and a general ledger?

- Explain the posting process.

- What is the accounting cycle?

NOTE: The purpose of these questions is to prepare you for the concepts introduced in the chapter. Your goal should be to answer each of these questions as you read through the chapter. If, when you complete the chapter, you are unable to answer one or more the Concept Self-Check questions, go back through the content to find the answer(s). Solutions are not provided to these questions.

2.1 Accounts

LO1 – Describe asset, liability, and equity accounts, identifying the effect of debits and credits on each.

Chapter 1 reviewed the analysis of financial transactions and the resulting impact on the accounting equation. We now expand that discussion by introducing the way transaction is recorded in an account. An account accumulates detailed information regarding the increases and decreases in a specific asset, liability, or equity item. Accounts are maintained in a ledger also referred to as the books. We now review and expand our understanding of asset, liability, and equity accounts.

Asset Accounts

Recall that assets are resources that have future economic benefits for the business. The primary purpose of assets is that they be used in day-to-day operating activities in order to generate revenue either directly or indirectly. A separate account is established for each asset. Examples of asset accounts are reviewed below.

- Cash has future purchasing power. Coins, currency, cheques, and bank account balances are examples of cash.

- Accounts receivable occur when products or services are sold on account or on credit. When a sale occurs on account or on credit, the customer has not paid cash but promises to pay in the future.

- Notes receivable are a promise to pay an amount on a specific future date plus a predetermined amount of interest.

- Office supplies are supplies to be used in the future. If the supplies are used before the end of the accounting period, they are an expense instead of an asset.

- Merchandise inventory are items to be sold in the future.

- Prepaid insurance represents an amount paid in advance for insurance. The prepaid insurance will be used in the future.

- Prepaid rent represents an amount paid in advance for rent. The prepaid rent will be used in the future.

- Land cost must be in a separate account from any building that might be on the land. Land is used over future periods.

- Buildings indirectly help a business generate revenue over future accounting periods since they provide space for day-to-day operating activities.

Liability Accounts

As explained in Chapter 1, a liability is an obligation to pay for an asset in the future. The primary purpose of liabilities is to finance investing activities that include the purchase of assets like land, buildings, and equipment. Liabilities are also used to finance operating activities involving, for example, accounts payable, unearned revenues, and wages payable. A separate account is created for each liability. Examples of liability accounts are reviewed below.

- Accounts payable are debts owed to creditors for goods purchased or services received as a result of day-to-day operating activities. An example of a service received on credit might be a plumber billing the business for a repair.

- Wages payable are wages owed to employees for work performed.

- Short-term notes payable are a debt owed to a bank or other creditor that is normally paid within one year. Notes payable are different than accounts payable in that notes involve interest.

- Long-term notes payable are a debt owed to a bank or other creditor that is normally paid beyond one year. Like short-term notes, long-term notes involve interest.

- Unearned revenues are payments received in advance of the product or service being provided. In other words, the business owes a customer the product/service.

Equity Accounts

Chapter 1 explained that equity represents the net assets owned by the owners of a business. In a corporation, the owners are called shareholders. Equity is traditionally one of the more challenging concepts to understand in introductory financial accounting. The difficulty stems from there being different types of equity accounts: share capital, retained earnings, dividends, revenues, and expenses. Share capital represents the investments made by owners into the business and causes equity to increase. Retained earnings is the sum of all net incomes earned over the life of the corporation to date, less any dividends distributed to shareholders over the same time period. Therefore, the Retained Earnings account includes revenues, which cause equity to increase, along with expenses and dividends, which cause equity to decrease. Figure 2.1 summarizes equity accounts.

T-accounts

A simplified account, called a T-account, is often used as a teaching/learning tool to show increases and decreases in an account. It is called a T-account because it resembles the letter T. As shown in the T-account below, the left side records debit entries and the right side records credit entries.

| Account Name | |

| Debit | Credit |

| (always on left) | (always on right) |

The type of account determines whether an increase or a decrease in a particular transaction is represented by a debit or credit. For financial transactions that affect assets, dividends, and expenses, increases are recorded by debits and decreases by credits. This guideline is shown in the following T-account.

For financial transactions that affect liabilities, share capital, and revenues, increases are recorded by credits and decreases by debits, as follows:

Another way to illustrate the debit and credit rules is based on the accounting equation. Remember that dividends, expenses, revenues, and share capital are equity accounts.

| Assets | = | Liabilities | + | Equity | |

| Increases are recorded as: | Debits | Credits | Credits1 | ||

| Decreases are recorded as: | Credits | Debits | Debits2 |

The following summary shows how debits and credits are used to record increases and decreases in various types of accounts.

| ASSETS | LIABILITIES |

| DIVIDENDS | SHARE CAPITAL |

| EXPENSES | REVENUE |

| Increases are DEBITED. | Increases are CREDITED. |

| Decreases are CREDITED. | Decreases are DEBITED. |

This summary will be used in a later section to illustrate the recording of debits and credits regarding the transactions of Big Dog Carworks Corp. introduced in Chapter 1.

The account balance is determined by adding and subtracting the increases and decreases in an account. Two assumed examples are presented below.

| Cash | Accounts Payable | ||||||

| 10,000 | 3,000 | 700 | 5,000 | ||||

| 3,000 | 3,000 | ||||||

| 400 | 2,400 | 4,300 | Balance | ||||

| 8,000 | 2,000 | ||||||

| 7,100 | |||||||

| 200 | |||||||

| Balance | 3,700 | ||||||

The $3,700 debit balance in the Cash account was calculated by adding all the debits and subtracting the sum of the credits. The $3,700 is recorded on the debit side of the T-account because the debits are greater than the credits. In Accounts Payable, the balance is a $4,300 credit calculated by subtracting the debits from the credits.

Notice that Cash shows a debit balance while Accounts Payable shows a credit balance. The Cash account is an asset so its normal balance is a debit. A normal balance is the side on which increases occur. Accounts Payable is a liability and because liabilities increase with credits, the normal balance in Accounts Payable is a credit as shown in the T-account above.

Chart of Accounts

A business will create a list of accounts called a chart of accounts where each account is assigned both a name and a number. A common practice is to have the accounts arranged in a manner that is compatible with the order of their use in financial statements. For instance, Asset accounts begin with the digit '1', Liability accounts with the digit '2'. Each business will have a unique chart of accounts that corresponds to its specific needs. Big Dog Carworks Corp. uses the following numbering system for its accounts:

| 100-199 | Asset accounts |

| 200-299 | Liability accounts |

| 300-399 | Share capital, retained earnings, and dividend accounts |

| 500-599 | Revenue accounts |

| 600-699 | Expense accounts |

2.2 Transaction Analysis Using Accounts

LO2 – Analyze transactions using double-entry accounting.

In Chapter 1, transactions for Big Dog Carworks Corp. were analyzed to determine the change in each item of the accounting equation. In this next section, these same transactions will be used to demonstrate double-entry accounting. Double-entry accounting means each transaction is recorded in at least two accounts where the total debits ALWAYS equal the total credits. As a result of double-entry accounting, the sum of all the debit balance accounts in the ledger must equal the sum of all the credit balance accounts. The rule that debits = credits is rooted in the accounting equation:

| ASSETS | = | LIABILITIES | + | EQUITY3 | |

| Increases are: | Debits | Credits | Credits | ||

| Decreases are: | Credits | Debits | Debits |

Illustrative Problem—Double-Entry Accounting and the Use of Accounts

In this section, the following debit and credit summary will be used to record the transactions of Big Dog Carworks Corp. into T-accounts.

| ASSETS | LIABILITIES |

| DIVIDENDS | SHARE CAPITAL |

| EXPENSES | REVENUE |

| Increases are DEBITED. | Increases are CREDITED. |

| Decreases are CREDITED. | Decreases are DEBITED. |

Transaction 1

Jan. 1 – Big Dog Carworks Corp. issued 1,000 shares to Bob Baldwin, a shareholder, for a total of $10,000 cash.

Analysis:

*Note: An alternate analysis would be that the issuance of shares causes equity to increase and increases in equity are always recorded as a credit.

Transaction 2

Jan. 2 – Borrowed $3,000 from the bank.

Analysis:

Transaction 3

Jan. 3 – Equipment is purchased for $3,000 cash.

Analysis:

Transaction 4

Jan. 3 – A truck was purchased for $8,000; Big Dog paid $3,000 cash and incurred a $5,000 bank loan for the balance.

Analysis:

Note: Transaction 4 involves one debit and two credits. Notice that the total debit of $8,000 equals the total credits of $8,000 which satisfies the double-entry accounting rule requiring that debits ALWAYS equal credits.

Transaction 5

Jan. 5 – Big Dog Carworks Corp. paid $2,400 cash for a one-year insurance policy, effective January 1.

Analysis:

Transaction 6

Jan. 10 – The corporation paid $2,000 cash to reduce the bank loan.

Analysis:

Transaction 7

Jan. 15 – The corporation received an advance payment of $400 for repair services to be performed as follows: $300 in February and $100 in March.

Analysis:

Transaction 8

Jan. 31 – A total of $10,000 of automotive repair services is performed for a customer who paid $8,000 cash. The remaining $2,000 will be paid in 30 days.

Analysis:

Transaction 9

Jan. 31 – Operating expenses of $7,100 were paid in cash: Rent expense, $1,600; salaries expense, $3,500; and supplies expense of $2,000. $700 for truck operating expenses (e.g., oil, gas) were incurred on credit.

Analysis:

Note: Each expense is recorded in an individual account.

Transaction 10

Jan. 31 – Dividends of $200 were paid in cash to the only shareholder, Bob Baldwin.

Analysis:

After the January transactions of Big Dog Carworks Corp. have been recorded in the T-accounts, each account is totalled and the difference between the debit balance and the credit balance is calculated, as shown in the following diagram. The numbers in parentheses refer to the transaction numbers used in the preceding section. To prove that the accounting equation is in balance, the account balances for each of assets, liabilities, and equity are added. Notice that total assets of $19,100 equal the sum of total liabilities of $7,100 plus equity of $12,000.

2.3 The Trial Balance

LO3 – Prepare a trial balance and explain its use.

To help prove that the accounting equation is in balance, a trial balance is normally prepared instead of the T-account listing shown in the previous section. A trial balance is an internal document that lists all the account balances at a point in time. The total debits must equal total credits on the trial balance. The form and content of a trial balance is illustrated below, using the account numbers, account names, and account balances of Big Dog Carworks Corp. at January 31, 2015. Assume that the account numbers are those assigned by the business.

| Big Dog Carworks Corp. | ||||

| Trial Balance | ||||

| At January 31, 2023 | ||||

| Acct. No. | Account | Debit | Credit | |

| 101 | Cash | $3,700 | ||

| 110 | Accounts receivable | 2,000 | ||

| 161 | Prepaid insurance | 2,400 | ||

| 183 | Equipment | 3,000 | ||

| 184 | Truck | 8,000 | ||

| 201 | Bank loan | $6,000 | ||

| 210 | Accounts payable | 700 | ||

| 247 | Unearned revenue | 400 | ||

| 320 | Share capital | 10,000 | ||

| 330 | Dividends | 200 | ||

| 450 | Repair revenue | 10,000 | ||

| 654 | Rent expense | 1,600 | ||

| 656 | Salaries expense | 3,500 | ||

| 668 | Supplies expense | 2,000 | ||

| 670 | Truck operation expense | 700 | ||

| $27,100 | $27,100 | |||

Double-entry accounting requires that debits equal credits. The trial balance establishes that this equality exists for Big Dog but it does not ensure that each item has been recorded in the proper account. Neither does the trial balance ensure that all items that should have been entered have been entered. In addition, a transaction may be recorded twice. Any or all of these errors could occur and the trial balance would still balance. Nevertheless, a trial balance provides a useful mathematical check before preparing financial statements.

Preparation of Financial Statements

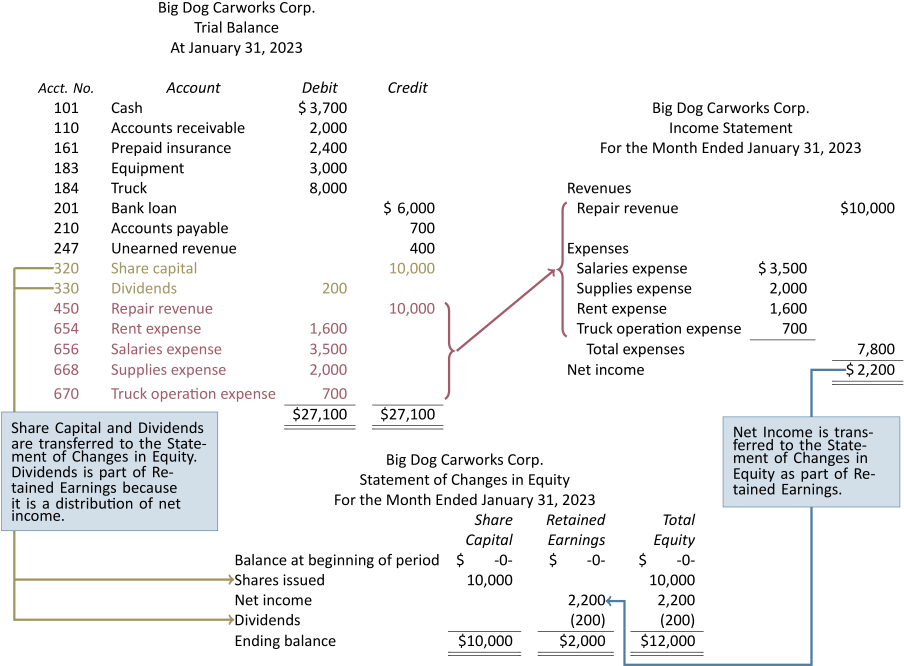

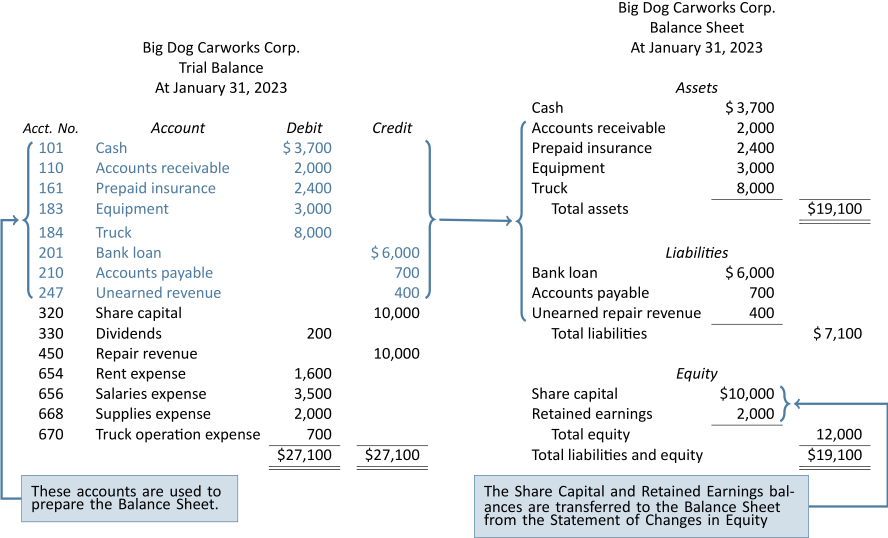

Financial statements for the one-month period ended January 31, 2023 can now be prepared from the trial balance figures. First, an income statement is prepared.

The asset and liability accounts from the trial balance and the ending balances for share capital and retained earnings on the statement of changes in equity are used to prepare the balance sheet.

NOTE: Pay attention to the links between financial statements.

The income statement is linked to the statement of changes in equity: Revenues and expenses are reported on the income statement to show the details of net income. Because net income causes equity to change, it is then reported on the statement of changes in equity.

The statement of changes in equity is linked to the balance sheet: The statement of changes in equity shows the details of how equity changed during the accounting period. The balances for share capital and retained earnings that appear on the statement of changes in equity are transferred to the equity section of the balance sheet.

The balance sheet SUMMARIZES equity by showing only account balances for share capital and retained earnings. To obtain the details regarding these equity accounts, we must look at the income statement and the statement of changes in equity.

2.4 Using Formal Accounting Records

LO4 – Record transactions in a general journal and post in a general ledger.

The preceding analysis of financial transactions used T-accounts to record debits and credits. T-accounts will continue to be used for illustrative purposes throughout this book. In actual practice, financial transactions are recorded in a general journal.

A general journal, or just journal, is a document that is used to chronologically record a business's debit and credit transactions (see Figure 2.2). It is often referred to as the book of original entry. Journalizing is the process of recording a financial transaction in the journal. The resulting debit and credit entry recorded in the journal is called a journal entry.

A general ledger, or just ledger, is a record that contains all of a business's accounts. Posting is the process of transferring amounts from the journal to the matching ledger accounts. Because amounts recorded in the journal eventually end up in a ledger account, the ledger is sometimes referred to as a book of final entry.

Recording Transactions in the General Journal

Each transaction is first recorded in the journal. The January transactions of Big Dog Carworks Corp. are recorded in its journal as shown in Figure 2.2. The journalizing procedure follows these steps (refer to Figure 2.2 for corresponding numbers):

- The year is recorded at the top and the month is entered on the first line of page 1. This information is repeated only on each new journal page used to record transactions.

- The date of the first transaction is entered in the second column, on the first line. The day of each transaction is always recorded in this second column.

- The name of the account to be debited is entered in the description column on the first line. By convention, accounts to be debited are usually recorded before accounts to be credited. The column titled 'F' (for Folio) indicates the number given to the account in the General Ledger. For example, the account number for Cash is 101. The amount of the debit is recorded in the debit column. A dash is often used by accountants in place of .00.

- The name of the account to be credited is on the second line of the description column and is indented about one centimetre into the column. Accounts to be credited are always indented in this way in the journal. The amount of the credit is recorded in the credit column. Again, a dash may be used in place of .00.

- An explanation of the transaction is entered in the description column on the next line. It is not indented.

- A line is usually skipped after each journal entry to separate individual journal entries and the date of the next entry recorded. It is unnecessary to repeat the month if it is unchanged from that recorded at the top of the page.

Most of Big Dog's entries have one debit and credit. An entry can also have more than one debit or credit, in which case it is referred to as a compound entry. The entry dated January 3 is an example of a compound entry.

Posting Transactions to the General Ledger

The ledger account is a formal variation of the T-account. The ledger accounts shown in Figure 2.3 are similar to what is used in electronic/digital accounting programs. Ledger accounts are kept in the general ledger. Debits and credits recorded in the journal are posted to appropriate ledger accounts so that the details and balance for each account can be found easily. Figure 2.3 uses the first transaction of Big Dog Carworks Corp. to illustrate how to post amounts and record other information.

- The date and amount are posted to the appropriate ledger account. Here the entry debiting Cash is posted from the journal to the Cash ledger account. The entry crediting Share Capital is then posted from the journal to the Share Capital ledger account.

- The journal page number is recorded in the folio (F) column of each ledger account as a cross reference. In this case, the posting has been made from general journal page 1; the reference is recorded as GJ1.

- The appropriate ledger account number is recorded in the folio (F) column of the journal to indicate the posting has been made to that particular account. Here the entry debiting Cash has been posted to Account No. 101. The entry crediting Share Capital has been posted to Account No. 320.

- After posting the entry, a balance is calculated in the Balance column. A notation is recorded in the column to the left of the Balance column indicating whether the balance is a debit or credit. A brief description can be entered in the Description column but this is generally not necessary since the journal includes a detailed description for each journal entry.

This manual process of recording, posting, summarizing, and preparing financial statements is cumbersome and time-consuming. In virtually all businesses, the use of accounting software automates much of the process. In this and subsequent chapters, either the T-account or the ledger account can be used in working through exercises and problems. Both formats are used to explain and illustrate concepts in subsequent chapters.

Special Journals and Subledgers

The general journal and the general ledger each act as a single all-purpose document where all the company's transactions are recorded and posted over the life of the company.

As was shown in Figure 2.2, various transactions are recorded to a general journal chronologically by date as they occurred. When companies engage in certain same-type, high-frequency transactions such as credit purchases and sales on account, special journals are often created in order to separately track information about these types of transactions. Typical special journals that companies often use are a sales journal, cash receipts journal, purchases journal and a cash disbursements journal. There can be others, depending on the business a company is involved in. The general journal continues to be used to record any transactions not posted to any of the special journals, such as:

- correcting entries

- adjusting entries

- closing entries

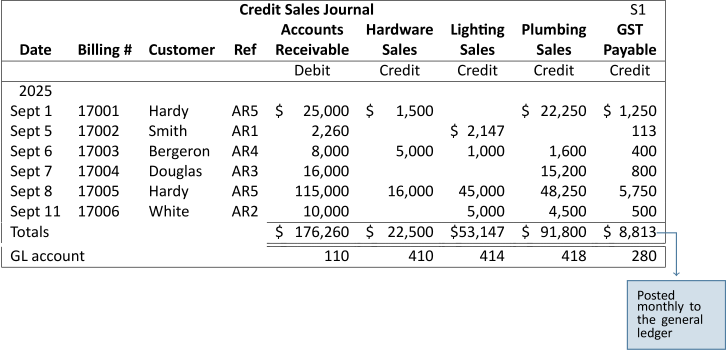

An example of a special journal for credit sales is shown below.

For simplicity, the cost of goods sold is excluded from this sales journal and will be covered in chapter five of this course. The sales journal provides a quick overview of the total credit sales for the month as well as various sub-groupings of credit sales such as by product sold, GST, and customers.

The sales journal can also be expanded to include credit sales returns, and the purchases journal to include purchases returns and allowances for each accounting month. Note that purchase discounts would be recorded in the cash disbursements journal because the discount is usually claimed at the time of the cash payment to the supplier/creditor. This is also the case with sales discounts from customers which would be recorded in the cash receipts journal at the time the cash, net of the sales discount, is received. Any cash sales returns would be recorded in the cash disbursements journal.

Recall from Figure 2.3 that with accounting records that comprise only a general journal and general ledger, each transaction recorded in the general journal was posted to the general ledger. With special journals, such as the sales journal, their monthly totals are posted to the general ledger instead. For larger companies, these journals can be summarized and posted more frequently, such as weekly or daily, if needed.

Below are examples of other typical special journals such as a purchases journal, cash receipts journal, cash disbursements journal and the general journal. Note the different sub-groupings in each one and consider how these would be useful for managing the company's business.

| Credit Purchases Journal | P1 | ||||||||||||

| Date | Invoice # | Creditor | Ref | Accounts Payable | Hardware Purchases | Lighting Purchases | Plumbing Purchases | GST Recv | |||||

| Credit | Debit | Debit | Debit | Debit | |||||||||

| 2025 | |||||||||||||

| Sept 1 | B253 | Better and Sons | AP6 | $ | 60,000 | $ | 57,000 | $ | 3,000 | ||||

| Sept 5 | 2008 | Northward Suppliers | AP2 | 160,000 | $ | 152,000 | 8,000 | ||||||

| Sept 6 | 15043 | Lighting Always | AP4 | 18,000 | $ | 17,100 | 900 | ||||||

| Sept 7 | RC18 | VeriSure Mfg | AP1 | 24,000 | 22,800 | 1,200 | |||||||

| Sept 8 | 1102 | Pearl Lighting | AP3 | 5,000 | 2,000 | 2,750 | 250 | ||||||

| Sept 11 | EF-1603 | Arnold Consolidated | AP5 | 1,600 | 1,520 | 80 | |||||||

| Totals | $ | 268,600 | $ | 154,000 | $ | 19,850 | $ | 81,320 | $ | 13,430 | |||

| GL account | 210 | 510 | 514 | 518 | 180 | ||||||||

| Cash Receipts Journal | CR1 | ||||||||||||

| Sales | Accounts | Cash | GST | ||||||||||

| Date | Billing # | Customer | Ref | Cash | Discount | Receivable | Sales | Payable | |||||

| Debit | Debit | Credit | Credit | Credit | |||||||||

| 2025 | |||||||||||||

| Sept 1 | 17001 | Hardy | AR5 | $ | 12,000 | $ | 120 | $ | 12,120 | ||||

| Sept 6 | CS1 | Cash sale | CS1 | 1,500 | $ | 1,425 | $ | 75 | |||||

| Sept 8 | 17003 | Bergeron | AR4 | 2,000 | 2,000 | ||||||||

| Sept 11 | 17004 | Douglas | AR3 | 20,000 | 20,000 | ||||||||

| Sept 12 | 17005 | Cash sale | CS2 | 3,250 | 3,088 | 163 | |||||||

| Sept 13 | 17006 | White | AR2 | 5,000 | 5,000 | ||||||||

| Totals | $ | 43,750 | $ | 120 | $ | 39,120 | $ | 4,513 | $ | 238 | |||

| GL account | 102 | 402 | 110 | 410 | 280 | ||||||||

| Cash Disbursements Journal | CD1 | |||||||||||

| Purchase | ||||||||||||

| Discount | Accounts | Other | ||||||||||

| Date | Chq # | Payee | Ref | Cash | (Inventory) | Payable | Disb... | Desc | ||||

| Credit | Credit | Debit | Debit | |||||||||

| 2025 | ||||||||||||

| Sept 1 | 101 | General Lighting Ltd. | AP22 | $ | 14,775 | $ | 225 | $ | 15,000 | |||

| Sept 2 | 102 | John Bremner | SAL1 | 1,600 | $ | 1,600 | Salary exp. | |||||

| Sept 11 | 103 | Lighting Always | AP4 | 4,200 | 4,200 | |||||||

| Sept 12 | 104 | VeriSure Mfg | AP1 | 22,500 | 225 | 22,725 | ||||||

| Sept 13 | 105 | Receiver General | AP 14 | 14,000 | 14,000 | GST Aug | ||||||

| Sept 14 | 106 | City of Edmonton | AP18 | 5,500 | 5,500 | Property Tax | ||||||

| Totals | $ | 62,575 | $ | 450 | $ | 41,925 | $ | 21,100 | ||||

| GL account | 102 | 104 | 210 | various | ||||||||

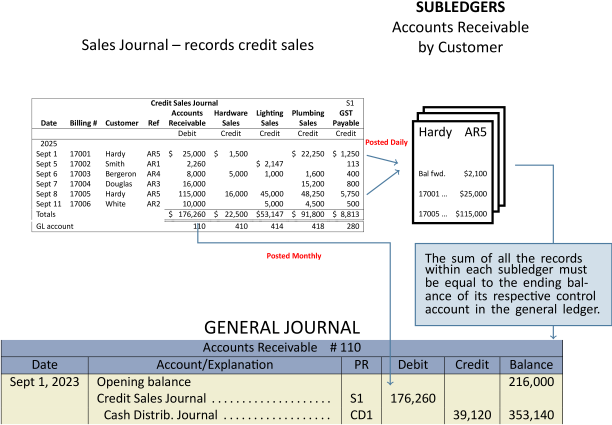

Each account that exists in the general journal must be represented by a corresponding account in the general ledger. As previously stated, each entry from the general journal is posted directly to the general ledger, if no other special journals or subledgers exist. If there are several hundreds or thousands of accounts receivable transactions for many different customers during a month, this detail cannot be easily summarized in meaningful ways. This may be fine for very small companies, but most companies need certain types of transactions sub-groupings, such as for accounts receivable, accounts payable and inventory. For this reason, subsidiary ledgers or subledgers are used to accomplish this. Subledgers typically include accounts receivable sub-grouped by customer, accounts payable by supplier, and inventory by inventory item. Monthly totals from the special journals continue to be posted to the general ledger, which now acts as a control account to its related subledger. It is critical that the subledgers always balance to their respective general ledger control account, hence the name control account.

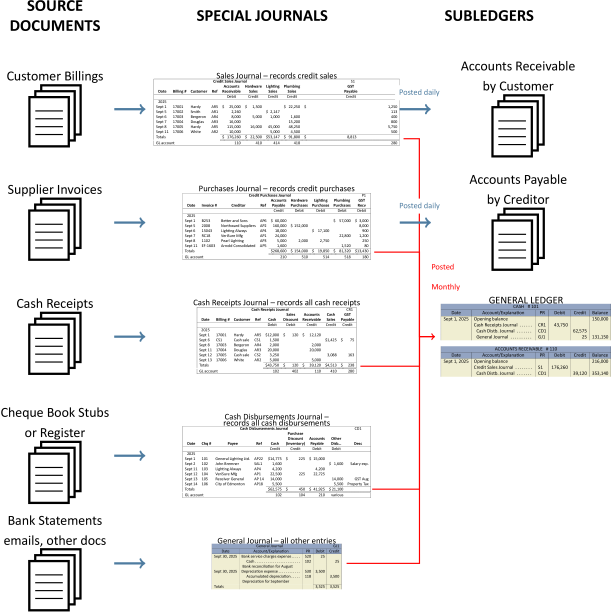

Below is an example of how a special journal, such as a sales journal is posted to the subledgers and general ledger.

Note how the general ledger can now be posted using the monthly totals from the sales journal instead of by individual transaction. Each line item within the sales journal is now posted on a daily basis directly to the subledger by customer instead, and balanced to the accounts receivable control balance in the general ledger. The subledger enables the company to quickly determine which customers owe money and details about those amounts.

At one time, recording transactions to the various journals and ledgers was all done manually as illustrated above. Today, accounting software makes this process easy and efficient. Data for each transaction is entered into the various data fields within the software transaction record. Once the transaction entry has been input and saved, the software automatically posts the data to any special journals, subledgers and general ledger. At any time, the accountant can easily obtain summary or detailed reports including a trial balance, accounts receivable by customer, accounts payable by creditor, inventory by inventory item, and so on.

Below is a flowchart that illustrates the flow of the information for a manual system from the source documents to the special journals, the subledgers and to the general ledger. This illustration also helps to give a sense of how the data would flow using accounting software.

2.5 The Accounting Cycle

LO5 – Define the accounting cycle.

In the preceding sections, the January transactions of Big Dog Carworks Corp. were used to demonstrate the steps performed to convert economic data into financial information. This conversion was carried out in accordance with the basic double-entry accounting model. These steps are summarized in Figure 2.9.

The sequence just described, beginning with the journalising of the transactions and ending with the communication of financial information in financial statements, is commonly referred to as the accounting cycle. There are additional steps involved in the accounting cycle and these will be introduced in Chapter 3.

Summary of Chapter 2 Learning Objectives

LO1 – Describe asset, liability, and equity accounts, identifying the effect of debits and credits on each.

Assets are resources that have future economic benefits such as cash, receivables, prepaids, and machinery. Increases in assets are recorded as debits and decreases as credits. Liabilities represent an obligation to pay an asset in the future and include payables and unearned revenues. Inrceases in liabilities are recorded as credits and decreases as debits. Equity represents the net assets owned by the owners and includes share capital, dividends, revenues, and expenses. Increases in equity, caused by the issuance of shares and revenues, are recorded as credits, and decreases in equity, caused by dividends and expenses, are recorded as debits. The following summary can be used to show how debits and credits impact the types of accounts.

LO2 – Analyze transactions using double-entry accounting.

Double-entry accounting requires that each transaction be recorded in at least two accounts where the total debits always equal the total credits. The double-entry accounting rule is rooted in the accounting equation: Assets = Liabilities + Equity.

LO3 – Prepare a trial balance and explain its use.

To help prove the accounting equation is in balance, a trial balance is prepared. The trial balance is an internal document that lists all the account balances at a point in time. The total debits must equal total credits on the trial balance. The trial balance is used in the preparation of financial statements.

LO4 – Record transactions in a general journal and post in a general ledger.

The recording of financial transactions was introduced in this chapter using T-accounts, an illustrative tool. A business actually records transactions in a general journal, a document which chronologically lists each debit and credit journal entry. To summarize the debit and credit entries by account, the entries in the general journal are posted (or transferred) to the general ledger. The account balances in the general ledger are used to prepare the trial balance.

LO5 – Define the accounting cycle.

Analyzing transactions, journalizing them in the general journal, posting from the general journal into the general ledger, preparing the trial balance, and generating financial statements are steps followed each accounting period. These steps form the core of the accounting cycle. Additional steps involved in the accounting cycle will be introduced in Chapter 3.

- Why is the use of a transactions worksheet impractical in actual practice?

- What is an 'account'? How are debits and credits used to record transactions?

- Some tend to associate "good" and "bad" or "increase" and "decrease" with credits and debits. Is this a valid association? Explain.

- The pattern of recording increases as debits and decreases as credits is common to asset and expense accounts. Provide an example.

- The pattern of recording increases and credits and decreases as debits is common to liabilities, equity, and revenue accounts. Provide an example.

- Summarise the rules for using debits and credits to record assets, expenses, liabilities, equity, and revenues.

- What is a Trial Balance? Why is it prepared?

- How is a Trial Balance used to prepare financial statements?

- A General Journal is often called a book of original entry. Why?

- The positioning of a debit-credit entry in the General Journal is similar in some respects to instructions written in a computer program. Explain, using an example.

- What is a General Ledger? Why is it prepared?

- What is a Chart of Accounts? How are the accounts generally arranged and why?

- List the steps in the accounting cycle.