10.2: The Nature of Criminal Law, Constitutional Rights, Defenses, and Punishment

- Page ID

- 24149

- Understand what crime is.

- Compare and contrast the differences between criminal law and civil law.

- Understand the constitutional protections afforded to those accused of committing a crime.

- Examine some common defenses to crime.

- Learn about the consequences of committing a crime.

- Explore the goals or purposes of punishment for committing a crime.

Imagine a bookkeeper who works for a physicians group. This bookkeeper’s job is to collect invoices that are due and payable by the physicians group and to process the payments for those invoices. The bookkeeper realizes that the physicians themselves are very busy, and they seem to trust the bookkeeper with the task of figuring out what needs to be paid. She decides to create a fake company, generate bogus invoices for “services rendered,” and send the invoices to the physicians group for payment. When she processes payment for those invoices, the fake company deposits the checks in its bank account—a bank account she secretly owns. This is a fraudulent disbursement, and it is just one of many ways in which crime occurs in the workplace. Check out "Hyperlink: Thefts, Skimming, Fake Invoices, Oh My!" to examine several other common embezzlement schemes easily perpetrated by trusted employees.

http://www.acfe.com/resources/view.asp?ArticleID=1

Think it couldn’t happen to you? Check out common schemes perpetrated by trusted employees in this article posted on the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners’ Web site.

When crime occurs in the workplace or in the context of business, the temptation might be to think that no one is “really” injured. After all, insurance policies can cover some losses. Sometimes people think that if the victims of embezzlement do not immediately notice the embezzlement, then they must not “need” the money anyhow, so no real crime has been committed. Of course, these excuses are just smokescreens. When an insurance company has to pay for a claim arising from a crime, the insurance company is injured, as are the victim and society at large. Similarly, the fact that wealthy people or businesses do not notice embezzlement immediately does not mean that they are not entitled to retain their property. Crime undermines confidence in social order and the expectations that we all have about living in a civil society. No crime is victimless.

A crime is a public injury. At the most basic level, criminal statutes reflect the rules that must be followed for a civil society to function. Crimes are an offense to civil society and its social order. In short, crimes are an offense to the public, and someone who commits a crime has committed an injury to the public.

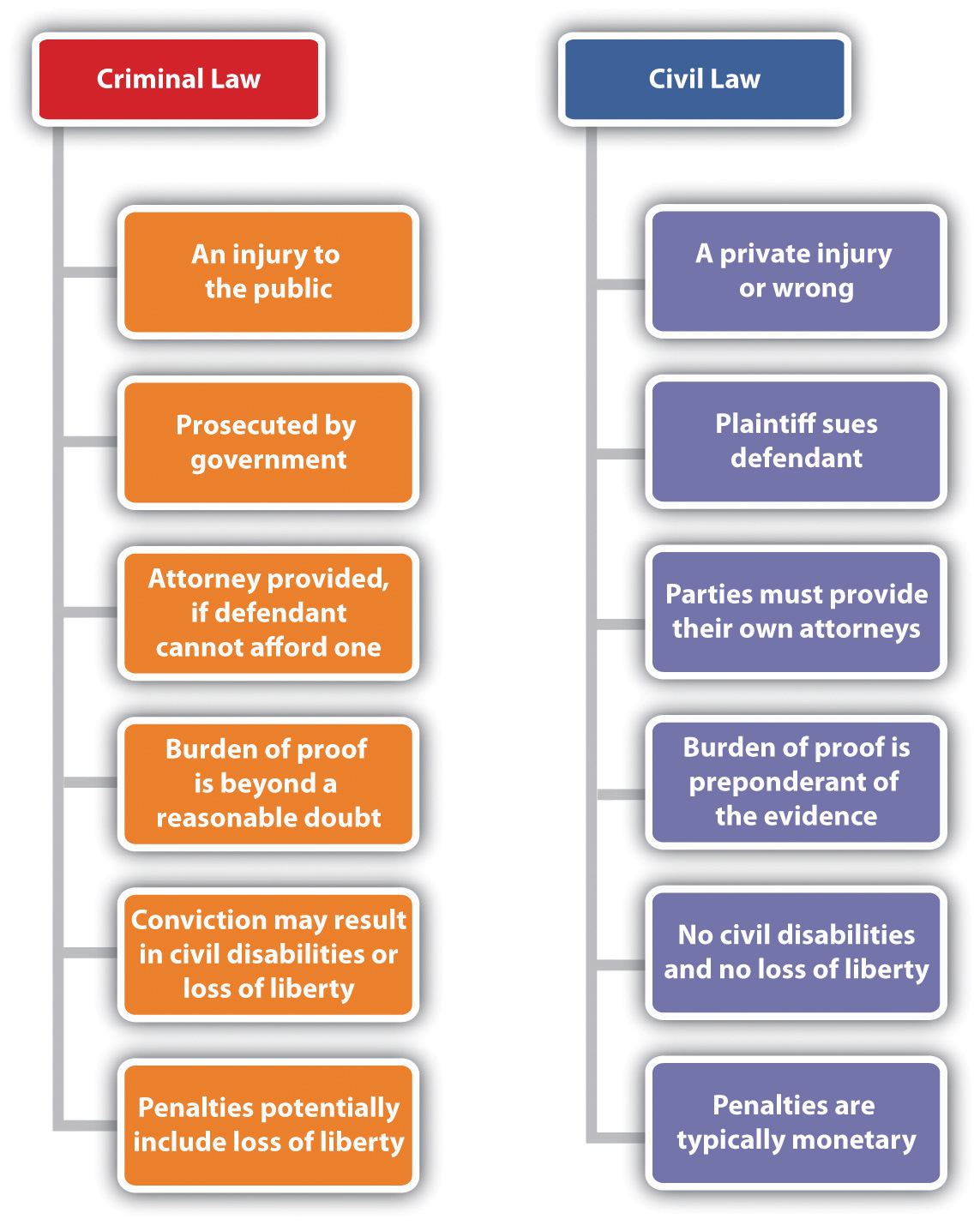

Criminal law differs from civil law in several important ways. See Figure 10.2.1 "Comparison between Criminal Law and Civil Law" for a comparison. For starters, since crimes are public injuries, they are punishable by the government. It is the government’s responsibility to bring charges against criminals. In fact, private citizens may not prosecute each other for crimes. When a crime has been committed—for instance, if someone is the victim of fraud—then the government collects the evidence and files charges against the defendant. When someone is charged with committing a crime, he or she is charged by the government in an indictment. The victim of the crime is a witness for the government but not for the prosecutor of the case. Note that our civil tort system allows a victim to bring a civil suit against someone for injuries inflicted on the victim by someone else. Indeed, criminal laws and torts often have parallel causes of action. Sometimes these claims carry the same or similar names. For instance, a victim of fraud may bring a civil action for fraud and may also be a witness for the state during the criminal trial for fraud.

In a criminal case, the defendant is presumed to be innocent unless and until he or she is proven guilty. This presumption of innocence means that the state must prove the case against the defendant before the government can impose punishment. If the state cannot prove its case, then the person charged with the crime will be acquitted. This means that the defendant will be released, and he or she may not be tried for that crime again. The burden of proof in a criminal case is the prosecution’s burden, and the prosecution must prove its case beyond a reasonable doubt. This means that the defendant does not have to prove anything, because the burden is on the government to prove its case. Additionally, the evidence must be so compelling that there is no reasonable doubt as to the defendant’s guilt. To be convicted of a crime, someone must possess the required criminal state of mind, or mens rea. Likewise, the person must have committed a criminal act, known as actus reus.

Compare this to the standard of proof in a civil trial, which requires the plaintiff to prove the case only by a preponderance of the evidence. This means that the evidence to support the plaintiff’s case is greater (or weightier) than the evidence that does not. It’s useful to think of the criminal standard of proof—beyond a reasonable doubt—as something like 99 percent certainty, with 1 percent doubt. Compare this to preponderance of the evidence, which we might think of as 51 percent in favor of the plaintiff’s case, but up to 49 percent doubt. This means that it is much more difficult to successfully prosecute a criminal defendant than it is to bring a successful civil claim. Since a criminal action and a civil action may be brought against a defendant for the same incident, these differences in burdens of proof can result in verdicts that seem, at first glance, to contradict each other. Perhaps the most well-known cases in recent history in which this very outcome happened were the O. J. Simpson trials. Simpson was acquitted of murder in a criminal trial, but he was found liable for wrongful death in a subsequent civil action. Check out "Hyperlink: Not Guilty Might Not Mean Innocent" for a similar result in the business context.

http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=20601103&sid=a89tFKR4OevM

Richard Scrushy of HealthSouth was acquitted of several criminal charges relating to accounting fraud but was found civilly liable for billions. He was subsequently found guilty in a later criminal case for different crimes committed.

This extra burden reflects the fact that the defendant in a criminal case stands to lose much more than a defendant in a civil case. Even though it may seem like a very bad thing to lose one’s assets in a civil case, the loss of liberty is considered to be a more serious loss. Therefore, more protections are afforded to the criminal defendant than are afforded to defendants in a civil proceeding. Because so much is at stake in a criminal case, our due process requirements are very high for anyone who is a defendant in criminal proceedings. Due process procedures are not specifically set out by the Constitution, and they vary depending on the type of penalty that can be levied against someone. For example, in a civil case, the due process requirements might simply be notice and an opportunity to be heard. If the government intends to revoke a professional license, then the defendant might receive notice by way of a letter, and the opportunity to be heard might exist by way of written appeal. In a criminal case, however, the due process requirements are higher. This is because a criminal case carries the potential for the most serious penalties.

Constitutional Rights Relevant to Criminal Proceedings

A person accused of a crime has several rights, which are guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution. Many crimes are state law issues. However, many provisions of the U.S. Constitution’s Bill of Rights, which contains the rights of concern to criminal defendants, have been incorporated as applicable to the states. This is known as the incorporation doctrine.

The Sixth Amendment guarantees that criminal defendants are entitled to an attorney during any phase of a criminal proceeding where there is a possibility of incarceration. This means that if a defendant cannot afford an attorney, then one is appointed for him or her at the state’s expense.

The Fifth Amendment guarantees the right to avoid self-incrimination. This right means that the government cannot torture someone accused of committing a crime. Obviously, someone under the physical and psychological pain of torture will admit to anything, and this might be a strong incentive to allow torture if the government wanted someone to confess to a crime. However, the Fifth Amendment guarantees that people can choose to remain silent. No one is compelled to testify against himself or herself to make self-incriminating statements.

The Eighth Amendment prohibits cruel and unusual punishment. We do not employ many techniques that were once used to punish people who committed crimes. For instance, we do not draw and quarter people, which was a practice in England during the Middle Ages. Recently, however, the question of the use of torture by the United States against aliens on foreign soil has been a hot topic. Many people believe that our Eighth Amendment protections should be extended to everyone held by U.S. authorities, whether they are on U.S. soil or not.

The Fourth Amendment provides a prohibition against illegal searches and seizures. This means that if evidence were obtained in violation of the Fourth Amendment, then it cannot be used against the defendant in a court of law. For Fourth Amendment requirements to be met, the government must first obtain a search warrant to search a particular area for particular items if there is a reasonable expectation of privacy in the area to be searched. The search warrant is issued only on probable cause. Probable cause arises when there is enough evidence, such as through corroborating evidence, to reasonably lead to the belief that someone has committed a crime.

If a valid search warrant is issued, then the government may search in the area specified by the warrant for the item that is the subject of the warrant. If a search occurs without a warrant, the search might still be legal, however. This is because there are several exceptions to the requirements for a search warrant. These include the plain view doctrine, exigent circumstances, consent, the automobile exception, lawful arrest, and stop and frisk. The plain view doctrine means that no warrant is required to conduct a search or to seize evidence if it appears in the plain view of a government agent, like a police officer. Exigent circumstances mean that no warrant is required in the event of an emergency. For instance, if someone is cruelly beating his dog, the state can remove the dog without a warrant to seize the dog. The exigent circumstances exception to the warrant requirement is used in hot pursuit cases. For example, if the police are in hot pursuit of a suspect who flees into a house, the police can enter the house to continue the pursuit without having to stop to first obtain a warrant to enter the house. Consent means that the person who has the authority to grant consent for a search or seizure has granted the consent. This does not necessarily have to be the owner of the location to be searched. For example, if your roommate consents to a search of your living room, which is a common area shared by you and your roommate, then that is valid consent, even if the police find something incriminating against you and you or your landlord did not consent to the search. The automobile exception means that an automobile may be searched if it has been lawfully stopped. When a police officer approaches a stopped car at night and shines a light into the interior of the car, the car has been searched. No warrant is required. If the police officer spots something that is incriminating, it may be seized without a warrant. Additionally, no warrant is required to search someone who is subject to lawful arrest. This exception exists to protect the police officer. For instance, if the police could not search someone who was just arrested, they would be in peril of injury from any weapon that the person in custody might have possession of. Similarly, if someone is stopped lawfully, that person may be frisked without a warrant. This is the stop and frisk exception to the warrant requirement.

In the business context, it is also important to note that administrative agencies in certain limited circumstances may conduct warrantless searches of closely regulated businesses, such as junkyards, where many stolen cars are disassembled for parts that can be sold.

Defenses

If the government violates a defendant’s constitutional rights when collecting evidence, then the evidence gathered in violation of those rights may be suppressed at trial. In other words, it may not be used against the defendant in trial. This is because evidence obtained through an illegal search is “fruit of the poisonous tree.” The fruit of the poisonous tree doctrine is known as the exclusionary rule. You should know, however, that lying to the defendant, or using forms of trickery and deceit, are not constitutional violations.

Another common defense arises under the exclusionary rule regarding confessions. This is when the government, while holding someone in a custodial interrogation, questions that person without first reading the Miranda warnings. If someone is subjected to a custodial interrogation, he or she must first be read the Miranda warnings, which you have probably heard in the movies. Though the U.S. Supreme Court did not script the warnings specifically, the warnings are usually delivered in language close to this: “You have the right to remain silent. Anything that you say can and will be used against you in a court of law. You have the right to an attorney. If you cannot afford an attorney, one will be provided to you by the state. Do you understand your rights?”

The purpose of the Miranda warnings is to ensure that people understand that they have the right not to make self-incriminating statements and that they have the right to have counsel. If someone wants to invoke his or her rights, he or she has to do so unequivocally. “Don’t I need a lawyer?” is not enough.

The Miranda warnings are not required unless someone is in custody and subject to interrogation. Someone in custody is not free to leave. So if a police officer casually strikes up a conversation with you while you are shopping in the grocery store and you happen to confess to a crime, that confession will be admissible as evidence against you even though you were not Mirandized. Why? Because you were not in custody and you were free to leave at any time. Likewise, if the police are not interrogating a person, then any statement made can also be used against that person, even if he or she is not Mirandized. Someone is being interrogated when the statements or actions by the police (or other government agent) are likely to give rise to a response.

Another defense provided by the U.S. Constitution is the prohibition against double jeopardy. The Fifth Amendment prohibits the government from prosecuting the same defendant for the same crime after he or she has already stood trial for it. This means that the government must do a very thorough job in collecting evidence prior to bringing a charge against a defendant, because unless the trial results in a hung jury, the prosecution will get only that one chance to prosecute the defendant.

Other defenses to crime are those involving lack of capacity, including insanity and infancy. Insanity is a lack of capacity defense, specifically applicable when the defendant lacks the capacity to understand that his actions were wrong. Infancy is a defense that may be used by persons who have not yet reached the age of majority, typically eighteen years of age. Those to which the infancy defense applies are not “off the hook” for their criminal actions, however. Juvenile offenders may be sentenced to juvenile detention centers for crimes they commit, with common goals including things like education and rehabilitation. In certain circumstances, juvenile offenders can be tried as adults, too.

Last, the state may not induce someone to commit a crime that he or she did not already have the propensity to commit. If the state does this, then the defendant will have the defense of entrapment.

Punishment

If convicted in a criminal case, the defendant will be punished by the government, rather than by the victim. Once a defendant is convicted of a crime, he or she is a criminal. Punishment for criminal offenses can include fines, restitution, forfeiture, probation, civil disabilities, and a loss of liberty. Loss of liberty means that the convicted criminal may be forced to do community service, may be subject to house arrest, may be incarcerated or, in some states that have the death penalty, may even lose his or her life.

Length of incarceration varies depending on whether the conviction was for a misdemeanor or a felony. A misdemeanor is a less serious offense than a felony, as determined by the legislative body and reflected in the relevant statutes. Even an infraction, such as a parking ticket, is a criminal offense, typically carrying a penalty of a fine. An infraction is considered less serious than a misdemeanor.

When someone is convicted of violating a state criminal statute—a felony, misdemeanor, or infraction—the penalty will be set by the statute. For instance, the statute might state that the punishment will be “up to $5,000” or “up to one year in jail.” Often, the possible punishments are given in a range, which allows the judge leeway to take other matters into consideration when sentencing the offender. For example, if someone is convicted of a misdemeanor that carries a penalty of up to one year in jail, but that person is a first-time offender with no prior criminal history, the judge might impose a sentence of some lesser time in jail, such as thirty days, or no jail time whatsoever.

Historically, all judges had the leeway to use their judgment when sentencing convicted criminals. However, disparities in sentences gave rise to concern about unequal treatment for similar offenses. In the 1980s the U.S. Sentencing Commission established the Federal Sentencing Guidelines, which were understood to be mandatory guidelines that federal judges were expected to use when sentencing offenders. The mandatory nature of these guidelines led some to observe that extremely harsh penalties were mandated for relatively minor offenses, given certain circumstances. Today, however, the federal guidelines are only advisory, due to the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in United States v. Booker, which held that a wide range of factors should be taken into consideration when sentencing offenders.United States v. Booker, 543 U.S. 220 (2005). This opinion restored to federal district court judges the power to exercise their judgment when sentencing federal offenders. Several states, however, passed their own versions of sentencing guidelines, and state trial court judges in those states must rely on those guidelines when sentencing state offenders. This has led to controversial “three strikes” laws, which can also carry extremely harsh penalties—such as incarceration for twenty-five years to life—for relatively minor offenses.

Often, the convicted criminal will be subject to various civil disabilities, depending on the state in which he or she lives. For instance, a felon, which is a criminal that has been convicted of a felony, may be prohibited from possessing firearms, running for public office, sitting on a jury, holding a professional license, or voting. A felon may be subject to deportation if he or she is an illegal immigrant.

Besides loss of liberty and civil disabilities, other forms of punishment exist. Some of these are also appropriate in civil cases. Punishment for crimes also includes a fine, which is a monetary penalty for committing an offense. Fines can also be levied in civil cases. Restitution, which is repayment for damage done by the criminal act, is a common punishment for property damage crimes such as vandalism. Restitution can also be an appropriate remedy in civil law, particularly in contracts disputes. Forfeiture, which means involuntarily losing ownership of property, is also a punishment, and it is commonly used in illegal drug trafficking cases to seize property used during the commission of a crime. Check out "Hyperlink: Shopping, Anyone?", which is the U.S. Marshall’s Assets Forfeiture page, to see forfeited property currently available for sale. Finally, probation is a common penalty for committing crime. Probation is when the criminal is under the supervision of the court but is not confined. Typically, the terms of the probation require the criminal to periodically report to a state agent, such as a probation officer.

www.usmarshals.gov/assets/assets.html

Purpose of Punishment

Conviction of a crime carries criminal penalties, such as incarceration. But what is the purpose of punishment? We do not have a vigilante system, where victims may bring their own form of justice to an offender. If we had such a system we would have never-ending feuds, such as the infamous and long-standing nineteenth-century dispute between the Hatfields and McCoys from the borderlands of West Virginia and Kentucky.

Several goals could be the focus of a criminal justice system. These could include retribution, punishment, rehabilitation, the protection of society, or deterrence from future acts of crime. Our criminal justice system’s penalties ostensibly do not exist for the purpose of retribution. Rather, rehabilitation, punishment, the protection of society, and deterrence from committing future crimes are the oft-cited goals. The Federal Bureau of Prisons captures some of these concepts in its mission statement. Federal Bureau of Prisons, “Mission and Vision of the Bureau of Prisons,” www.bop.gov/about/mission.jsp (accessed September 27, 2010). Sadly, rehabilitation programs are not always available or, when they are, they are not always considered appropriate—or, when appropriate, they do not always work. Additionally, the goal of deterrence is not always achieved, as reflected in high recidivism rates in the United States.

Punishment of Business-Related Crime

Punishments committed by “white-collar criminals” are the same as those committed by any criminal. White-collar crime is a term used to describe nonviolent crimes committed by people in their professional capacity or by organizations. Individuals involved in white-collar crime are criminally liable for their own actions.

Additionally, since a corporation is a legal person, then the corporation can be convicted of committing crimes, too. Accordingly, corporations can be punished. However, not all constitutional protections afforded to individuals are available to corporations. For instance, a corporation does not have the right against self-incrimination.

One difficulty that arises is the question of how to punish a corporation for engaging in criminal activity. After all, as they say, a corporation does not have a soul to rehabilitate or a body to incarcerate. Albert W. Alschuler, “Two Ways to Think about the Punishment of Corporations,” American Criminal Law Review, Public Law and Legal Theory Series, No. 09-19, 2009, p. 13, http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1491263 (accessed September 27, 2010).This is a paraphrase of a remark first uttered by Lord Chancellor Thurlow between 1778 and 1792: “No soul to damn, no body to kick.” This is very different from a human being, who will stand to lose his or her liberty or who might be subject to mandatory counseling.

We might argue that a criminal corporation should have its corporate charter revoked, which would be equivalent to a corporate death penalty. However, if that happened, a lot of innocent people who were not involved in the criminal activity would be harmed. For instance, employees would lose their jobs, and suppliers and customers would lose the goods or services of the corporate criminal. Entire communities could suffer the consequences of a few bad actors.

On the other hand, corporations must be punished to respect the goal of deterrence of future crimes. One way that corporations are deterred is by the imposition of hefty fines. It is not uncommon to base such penalties on some percentage of profits, or all profits derived from the ill-gotten gains of criminal activity.

Corporations that are criminals also lose much in the way of reputation. Of course, reputational damage can be very difficult to repair.

Key Takeaways

Crime is a public injury. Criminal law differs from civil law in important ways, including who brings the claim, the burden of proof, due process, postconviction civil disabilities, and penalties. Those who are accused of committing a crime are afforded a high level of due process, including constitutional protections against illegal searches and seizures, and self-incrimination; guarantee of an attorney; and prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment. Several common defenses to crimes exist. If convicted, criminals can face loss of liberty, with sentencing structures based on statutory language and, in the federal system, guided by the U.S. Federal Sentencing Guidelines. The goals of imposing penalties for violating criminal laws include protecting society, punishing the offender, rehabilitating the offender, and deterrence from future acts of crime. Corporations can also be convicted of crimes, though unique questions relating to appropriate means of punishment arise in that context.

- Imagine a woman who suffers from dementia and lives in an assisted living facility. One day, she wanders into another resident’s room and picks up an antique vase from the other resident’s bureau. As she holds the vase, she forgets that it belongs to someone else and walks out of the room with it. Later, she places it on her own nightstand, where she admires it greatly. Has there been a crime here? Why or why not?

- Consider the case of O. J. Simpson, in which a criminal jury acquitted him of murder, but a civil court found him liable for wrongful death. Both trials arose out of the same incident. Do you think that the burden of proof should be the same for a civil case as it is for a criminal case? Why?

- What should be the goal of penalties or punishments for criminal offenses? Compare and contrast how our criminal justice system would differ if the goal of punishment was each of the following: retribution, rehabilitation, protection of society, or deterrence from future acts of crime.

- Consider the difference between minimum security federal prison camps and medium or high-level securities facilities, described here: www.bop.gov/locations/institutions/index.jsp. Should white-collar criminals receive the same punishment as those convicted of committing a violent crime? Why or why not?

- Before listening to the link in this assignment, write down your perceptions of “federal prison camp.” Then, listen to an interview with a convicted white-collar criminal here: discover.npr.org/features/feature.jhtml?wfId=1149174. Compare your initial perceptions with what you have learned from this interview. How are they the same? How do they differ?

- How should a corporation be punished for committing a crime? Find an example of a corporation that was convicted of a crime. Do you believe that the punishment was appropriate? Discuss.

- What kinds of crimes do college students commit? While the vast majority of college students wouldn’t even think of committing a violent crime, many students do engage in crimes they believe to be victimless, such as downloading movies or buying and selling prescription drugs like Adderall or Ritalin. Are these crimes actually victimless?

- The exclusionary rule was created by the Supreme Court as a means of punishing the police for violating a defendant’s constitutional rights. Some legal commentators, including several members of the Supreme Court, believe the exclusionary rule should be abolished. Without it, how do you think society can ensure the police will not violate a citizen’s constitutional rights?