13.2: The Nature of International Law

- Page ID

- 24170

- Compare and contrast the structure of international law with that of domestic law.

- Understand the difference between international law between states and law as it applies to businesses operating internationally.

Imagine hearing allegations that your company’s products are being assembled overseas in working conditions that have resulted in extreme despondency among workers, including several suicides. This is precisely the situation that Apple, Dell, Hewlett-Packard, and others find themselves in. Foxconn, which is part of the Taiwan-based Hon Hai Precision Industry Co., operates a large electronics assembly complex in China. Allegations have arisen that harsh working conditions have led to a string of suicides. If true, should these U.S. companies find another electronics manufacturer to assemble their products? Do consumers have any voice in this matter?

From your seat, it may seem like an obvious point that businesses should follow the laws and behave ethically in their business dealings if they wish to be successful for the long haul. However, when we look at the question of how a company might “follow the law,” we need to consider which laws we are referring to. When a U.S. company conducts business in another country, it must comply with applicable U.S. law, and with the law of the foreign nation where it is located. Several U.S. laws apply to the business activities of U.S. companies operating on foreign soil. However, it is perfectly legal for a U.S. company to contract with an overseas manufacturer for labor, without insisting that those workers are paid a wage equal to the U.S. federal minimum wage. In the case of Hon Hai and Foxconn, none of the U.S. companies can get into legal trouble regarding the fact that, until very recently, the average worker there made the equivalent of $132 per week, which is, of course, far below the U.S. federal minimum wage.Ting-I Tsai, “Hon Hai Gives Workers a Raise,” Wall Street Journal, May 29, 2010, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703957604575272454248180106.html?mod=WSJ_hpp_sections_tech (accessed September 27, 2010). There are several reasons for this.

Imagine that Apple alleged that labor conditions were not contractually satisfied and, therefore, Foxconn and Hon Hai Precision Industry Co. breached the agreement that they had made with Apple. If this were the case, Apple may wish to terminate its relationship with these companies. However, it is unlikely that the Asian companies would agree. This means that a dispute could arise under a contract between international parties. If Foxconn and Hon Hai disputed this allegation, which rule of law should govern the dispute? In the United States, contracts laws are state law rather than federal law, so should the laws of a particular state, like California, be applied to this dispute? Or should Chinese law apply? This can be a complicated question for several reasons. However, it is necessary to first examine of the nature of international law to understand this complexity. Try to make a distinction between the nature of international law between nation-states and the nature of law as it applies to businesses operating in the international arena. In the next section, we will return to the question of which type of law should apply to disputes in international contracts.

The Basics of International Law between Nation-States

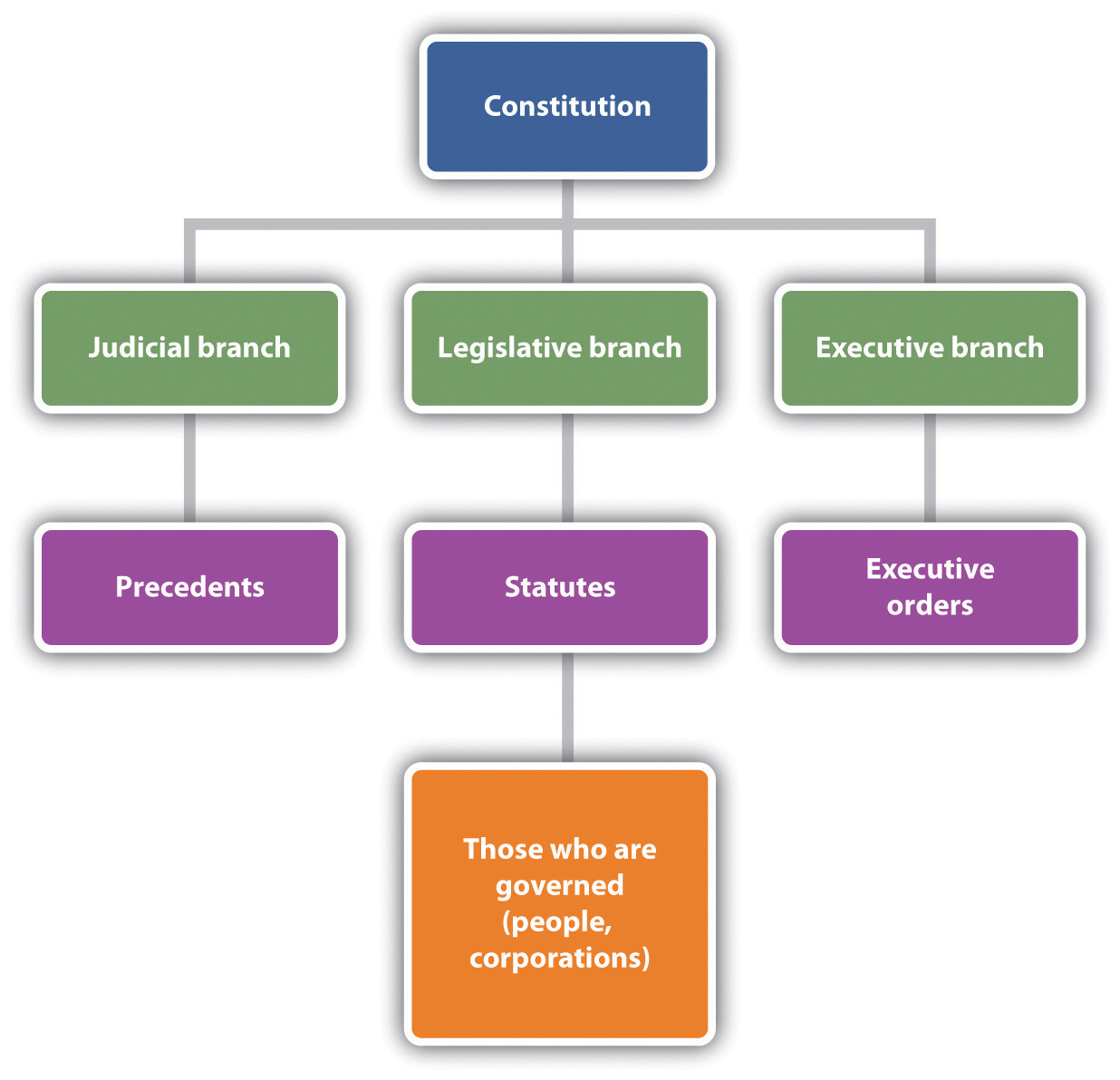

We are all subject to domestic laws, because we all live in a sovereign state. A sovereign state is a political entity that governs the affairs of its own territory without being subjected to an outside authority. Countries are sovereign states. The United States, Mexico, Japan, Cambodia, Chile, and Finland are all examples of sovereign states. In domestic law, or law that is applicable within the nation where it is created, some legitimate authority has the power to create, apply, and enforce a rule of law system. There is a legitimate law-creating authority at the “top,” and the people to be governed at the “bottom.” The law might be conceived of as being “handed down” to the people within its jurisdiction. This is a vertical structure of law, because there is some “higher” authority that imposes a rule of law on the people. In the United States, laws are handed down by the legislative branch in the form of statutory law, by the judicial branch in the form of common law, and by the executive branch in the form of executive orders, rules, and regulations. These government branches have legitimate authority to create a rule of law system, and this authority is derived from the U.S. Constitution. See Figure 13.2.1 "The Vertical Nature of U.S. Domestic Law" for a simple illustration of the vertical nature of domestic law in the United States. Of course, people can influence who become members of the branches of government through elections and which issues are brought before government to consider and possibly legislate, but that does not change the fact that people are subjected to laws that are handed down in a vertical nature.

It’s important to note, however, that not all law can be conceived as a vertical structure. Some laws, such as international law, or law between sovereign states, are best thought of in a horizontal structure. For example, treaties have a horizontal structure. This is because the parties to international treaties are sovereign states. Since each state is sovereign, that means that one sovereign state is not in a legally dominant or authoritative position over the other. See Figure 13.2.2 "An Illustration of the Horizontal Nature of International Law between Nation-States" for an illustration of the horizontal nature of international law between nation-states, using the North American Free Trade Agreement as an example.

An obvious challenge to laws created in horizontal power structures that lie outside of any legitimate lawmaking authority “above” the parties is that enforcement of violations can be difficult. For this reason, many horizontal laws, like treaties, contain provisions that require the parties to the treaty to submit to a treaty-created dispute resolution panel or other neutral tribunal, such as the International Court of Justice (ICJ). Though it is common for treaties to set forth expectations that disputes will be heard before some predesignated tribunal, some international relations experts believe that the state of international law is one of persistent anarchy.

Examine the differences between vertical structure and horizontal structures of law. Consider the case of a criminal in the United States. The criminal can be prosecuted by the laws of the United States (federal or state, depending on the jurisdiction of the offence) and, if convicted, will have to submit to the authority of the United States for punishment. This is because we recognize that there is some legitimate authority in domestic law that allows the U.S. government to exact punishment against convicted criminals. Compare this to a sovereign state that violates a treaty agreement. For example, perhaps a member of a treaty has broken its treaty promise to refrain from fishing in a certain fishery. Since in the international arena there is no overarching power “above” the parties to a treaty, enforcement of treaty agreements can be difficult.

Another common challenge in international law is that the laws are applicable only to parties who voluntarily choose to participate in them. This means that a sovereign state cannot generally be compelled to submit to the authority of the international law if it chooses not to participate. Compare this with domestic law. Everyone within the United States, for example, is subject to the jurisdiction of certain state and federal courts, whether they voluntarily choose to submit to jurisdiction or not. This is why fleeing criminals can legitimately be caught and brought to justice in domestic law through extradition.

The Nature of Law as It Applies to Businesses Operating in the International Arena

Businesses are not involved in signing treaties or in creating law that applies between sovereign states. Indeed, the sovereign states themselves have the only power to conduct foreign affairs. In the United States, that power rests with the president, though Congress also has important roles. For example, the Senate must ratify a treaty before the treaty binds the United States and before its provisions become law for the people within the United States.

However, businesses are required to abide by their own applicable domestic laws as well as the laws of the foreign country in which they are conducting business. When domestic laws apply to businesses operating internationally, that is a vertical legal structure, such as is illustrated in Figure 13.2.1 "The Vertical Nature of U.S. Domestic Law". This is because there is a legitimate authority over the business that governs its behavior.

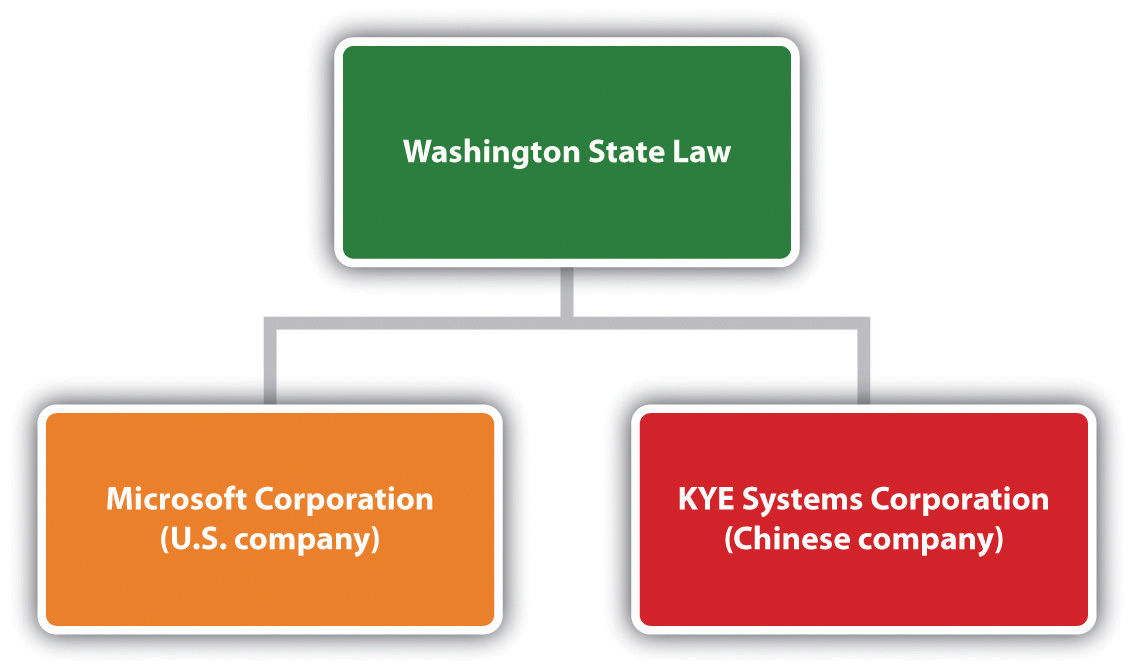

As noted in the example concerning U.S. companies doing business with Foxconn and Hon Hai Precision Industry Co., international business can involve creating contracts between parties from different nations. These contracts are horizontal in nature, much like a treaty. However, they are also subject to a vertical legal structure, because the parties to the contact will have chosen which laws will apply to resolve disputes arising under the contract. For example, if Microsoft, a U.S. company, has a contract with KYE Systems Corp., a Chinese manufacturer, to assemble its products, the contract might very well include a choice of law clause that would require any contract dispute to be settled in accordance with Washington State law. A choice of law clause is a contractual provision that specifies which law and jurisdiction will apply to disputes arising under the contract. The contract might contain such a clause because Microsoft’s headquarters are in Washington State, and it would be more convenient for Microsoft to settle any disputes arising under a contract by using the laws in the state where it is located. This probably would be terribly inconvenient for KYE Systems Corp., but the benefits of obtaining a Microsoft contract probably outweigh the potential inconvenience of resolving disputes in the Washington State court system. Additionally, a well-established United Nations treaty, the Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards, provides for the enforcement of arbitral awards among member states. That means Microsoft and KYE Systems Corp. could agree in a predispute arbitration clause, perhaps in a purchase order or invoice, to arbitrate their disputes in Washington, using Washington contract law, and in English. The prevailing party in the arbitration could take the award to court in either Washington or China and convert it into a legally binding judgment under the treaty. Choice of law clauses have consequences regarding the way the contract will be interpreted in the event of a dispute, costs associated with defending a complaint arising under a contract, and convenience. See Figure 13.2.3 "The Horizontal and Vertical Nature of Contract Relationships in the Global Legal Environment" for an illustration of the horizontal and vertical nature of contract law in international business.

Key Takeaways

While international law between sovereign states is relevant to business in many ways—for instance, it would be illegal for a company to ignore the terms of a treaty that its own country had ratified—the types of law that are relevant to businesses operating in the international environment are domestic laws. A choice of law clause within the contract designates which country’s law will apply to a dispute arising under an international contract.

- If you were creating a contract with a supplier in a different country, what types of things would you consider when deciding on the choice of law clause?

- Check out www.ustr.gov/trade-agreements/free-trade-agreements/north-american-free-trade- agreement-nafta. How might this international law present opportunities for businesses in the United States that might wish to export or import products to or from Canada or Mexico?

- Could a U.S. state enter into a treaty with a sovereign nation outside the United States? Why or why not?